The phrase ‘the Amazon effect’ brings to mind images of boarded-up shops and retail bankruptcies.

We think of the 2,700 stores that shut or the 80,000 retail jobs that disappeared in the UK in the first half of 2018 alone. E-commerce, and Amazon in particular, is often positioned as the death knell for the high street.

I don’t buy into the ‘retail apocalypse’ narrative, but it must be acknowledged that this is a period of unprecedented change and naturally as spending shifts online, fewer stores are needed.

I don’t buy into the ‘retail apocalypse’ narrative, but it must be acknowledged that this is a period of unprecedented change and naturally as spending shifts online, fewer stores are needed.

This isn’t rocket science, it is just about following the customer. Over the past five years, online sales of non-food products in the UK have doubled. Now, nearly 20% of all retail sales take place online. Today, people are ubiquitously connected. They live online. They have access to billions of products right at their fingertips that turn up on doorsteps, often free of charge, the very next day.

Online shopping has become utterly effortless, and that has shaken bricks-and-mortar retail to its core. 2018 was the year that retail chief executives finally pulled their heads out of the sand and acknowledged that there is an oversupply of retail space and there is retail space that is no longer fit for purpose.

Blaming Amazon

Amazon is an easy scapegoat. After all, it’s thought that around a third of UK e-commerce sales go through Amazon’s platform (in the US, it’s closer to the 50% mark).

And, after years of chipping away at the high street, Amazon is now among the top five retailers in the UK. Not many retailers can match ‘the everything store’ on range, convenience and, perhaps to a lesser extent, price. Not many retailers have 100 million customers around the globe willing to fork out roughly $100 annually just for the privilege of shopping with them. Not many have embedded themselves into the shopper’s life – and physical home – in the way that Amazon has; a testament to the strength of its ecosystem.

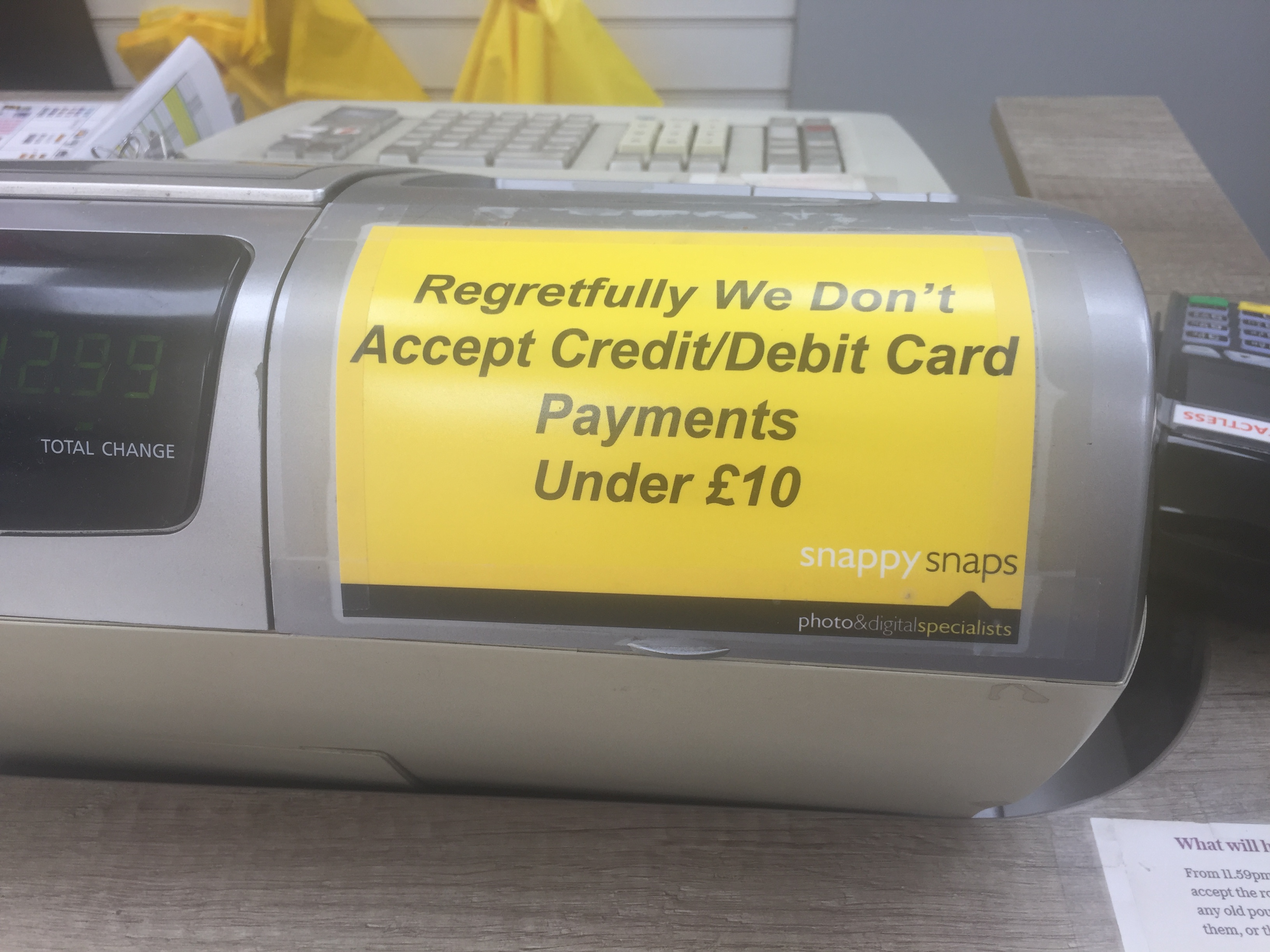

But it is also true that not many retailers have deep pockets like Amazon – it spends more on R&D than any other American company. It is able to constantly throw ideas against the wall because it has been afforded the luxury of long-term thinking – and not paying a whole lot of tax hasn’t hurt. Business rates account for less than 1% of its sales (for comparison, Debenhams’ bill as a percentage of sales is almost 4 times that amount). The playing field has been tilted in Amazon’s favour since day one and I believe retailers are right to call for legislation to be rewritten for the digital age.

High street woes go beyond Amazon

But the industry’s problems run deeper than Amazon. Retailers continue to grapple with the dangerous combination of rising costs and soft demand which has created considerable pressure and particularly exposed some of the weaker retailers with underlying issues, such as Toys R Us.

Real disposable income growth has been weak for a good decade and now the big unknown that is Brexit is added to the mix. In a similar vein to the weather, Brexit may be a convenient excuse for retailers reporting weak results, but it’s clear that shoppers will rein in spending during times of political and economic uncertainty.

What else is behind the high street’s woes? Although ‘the Amazon effect’ is often cited, what about ‘the Aldi effect’ or ‘the Primark effect’? There are a handful of very agile bricks-and-mortar disruptors that are weeding out the complacent incumbents.

We are at the beginning of quite a fundamental shift in consumer values, as shoppers prioritise spending on experiences over simply acquiring more material goods. Are we perhaps nearing ‘peak stuff’?

In any case, it’s clear we are at the intersection of major technological, economic and societal changes that are profoundly reshaping the retail sector.

Amazon isn’t killing retail, it’s killing mediocre retail

So it’s not all Amazon’s fault. In fact, in many ways Amazon has been a force for good. It has stamped out complacency and made everyone raise their game, all to the benefit of the customer.

What would retail look like if Amazon didn’t exist? In a nutshell, consumers would be more tolerant of mediocre service.

Amazon’s technology roots and passion for invention are what sets it distantly apart from rivals. Many of Amazon’s past innovations can, in fact, be easily forgotten because they have simply become today’s normal. Think back to the late 1990s: online shopping used to be quite a laborious process. Amazon cut the friction out by launching one-click shopping, personalised product recommendations and user-generated ratings and reviews.

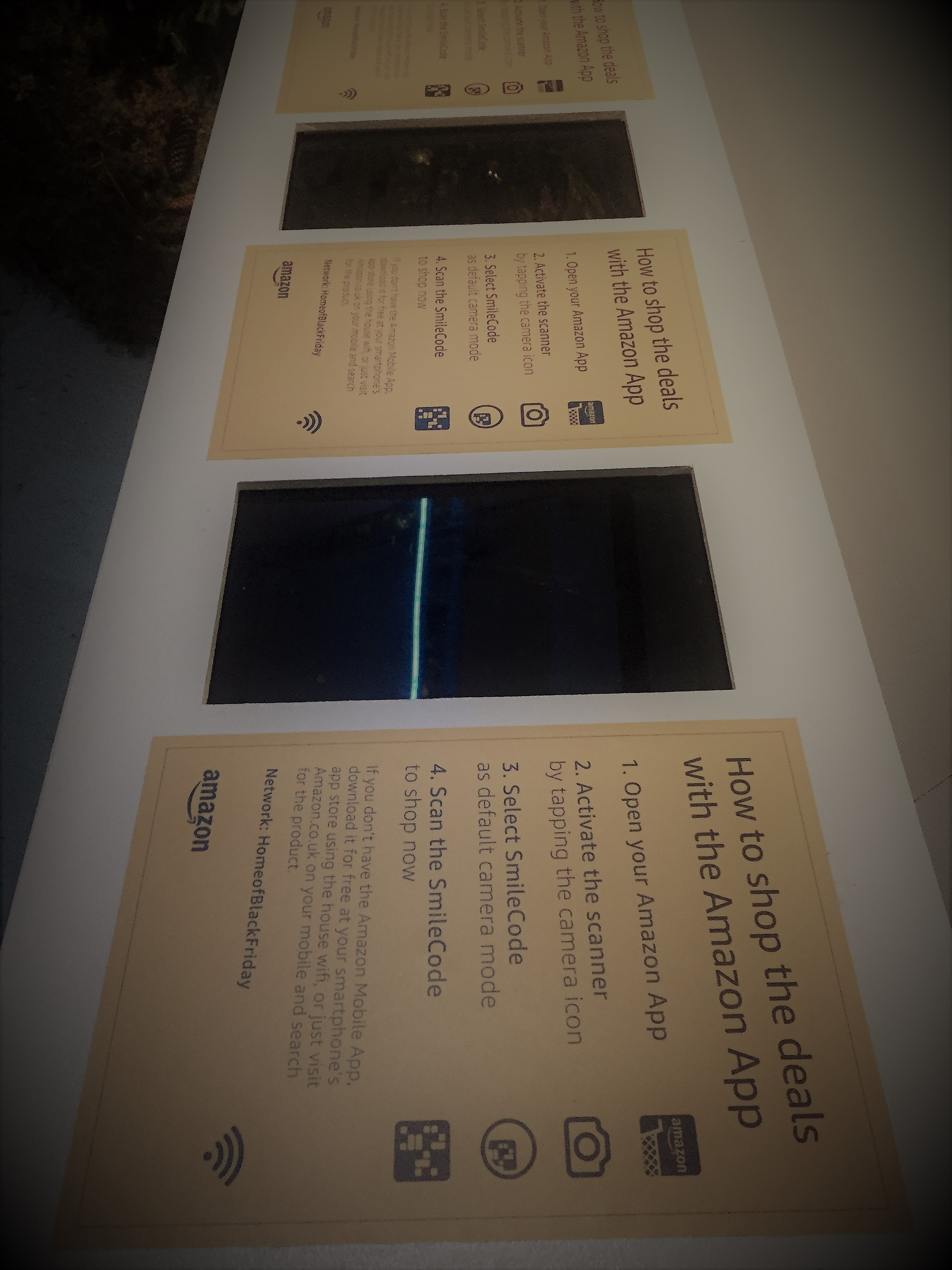

Delivery, meanwhile, wasn’t always fast and free. Prime significantly raised customer expectations, leaving competitors with little choice but to invest in their own fulfilment capabilities. Amazon went on to tackle one of the biggest barriers to online shopping – missed deliveries – with the 2011 launch of Amazon Lockers. Today, virtually every major Western retailer offers click-and-collect (though Argos was perhaps unknowingly ahead of its time).

Most of Amazon’s innovations catch competitors on the back foot, leaving them in the undesirable position of reacting to rather than leading change. So what is ‘the Amazon effect’, really?

It’s Tesco rolling out same-day delivery nationwide.

It’s M&S trialling scan-and-go technology, allowing shoppers to skip checkout queues ahead of an impending Amazon Go launch in London.

It’s Waitrose delivering groceries directly into your fridge.

It’s Asos allowing shoppers to ‘try before they buy’.

It’s Zara shoppers collecting their online orders through automated pick-up points in-store.

And this is a global battle. ‘The Amazon effect’ is Ocado finally securing a string of international deals, as the Amazon-Whole Foods acquisition accelerates demand for online grocery shopping.

It’s Carrefour partnering with Google to launch Lea – its answer to Amazon’s Alexa voice assistant. In the US, Walmart offers customers a far superior experience today thanks to Amazon breathing down its neck. The retailer has even had a name change: after nearly half a century as Wal-Mart Stores, in 2018 the world’s largest retailer dropped Stores from its legal name to reflect the new digital era.

Amazon has impacted all aspects of retail, and now everyone is scrambling to either keep up with or distance themselves from the online behemoth. The link may be slightly more tenuous but it could even be argued that ‘the Amazon effect’ is Debenhams adding gyms and beauty bars to its stores. It’s John Lewis sending staff to theatre training and democratising personal shopping. It’s Next putting hair salons and Prosecco bars in its shops.

The opportunity

High street retailers are recognising that for all its perks, shopping on Amazon is still quite a functional, transactional experience. It has taken the touch and feel out of shopping and there is a massive opportunity for retailers to distance themselves from Amazon’s utilitarian image.

There is an opportunity to inject some personality and soul back into their stores, providing an immersive, memorable experience that simply can’t be replicated online. It’s about WACD: What Amazon Can’t Do.

This is why in the future, stores won’t just be a place to buy but also a place to eat, play, work, discover, learn and even borrow stuff. Retail space will be less about retail.

In summary, Amazon is almost singlehandedly redefining retail, at least in the Western world. Yes, there have been casualties and the industry should brace itself for more short-term pain as it reconfigures itself for the digital age.

But this is retail Darwinism, it’s survival of the fittest. It’s evolve or die. Amazon’s existence has weeded out those underperforming retailers who can’t deliver on the basic principles of being relevant to their customers or standing out from rivals. But those left standing will be stronger for having reinvented themselves in the age of Amazon.

Amazon: How the world’s most relentless retailer will continue to revolutionize commerce, by Natalie Berg and Miya Knights, is published this month by Kogan Page.

A version of this article originally appeared in Retail Week

This year’s high-profile collapses of Maplin and Toys R Us made it more difficult to source some of the more peculiar items on the list – ie. build your own robot arm. The superstores I visited also, unsurprisingly, had a much-reduced electronics section as this category has largely shifted online.

This year’s high-profile collapses of Maplin and Toys R Us made it more difficult to source some of the more peculiar items on the list – ie. build your own robot arm. The superstores I visited also, unsurprisingly, had a much-reduced electronics section as this category has largely shifted online.

Why the big push into private label? It will help Amazon inch closer to sustained profitability. With its own brands, Amazon can widen margins without raising prices. It gives them greater leverage over suppliers and allows them to sweeten the deal for Prime members, as many own label items are sold exclusively to them. With the sheer amount of customer data Amazon holds, no one is better positioned to understand customer needs and then develop ranges specifically for them.

Why the big push into private label? It will help Amazon inch closer to sustained profitability. With its own brands, Amazon can widen margins without raising prices. It gives them greater leverage over suppliers and allows them to sweeten the deal for Prime members, as many own label items are sold exclusively to them. With the sheer amount of customer data Amazon holds, no one is better positioned to understand customer needs and then develop ranges specifically for them.

I believe entire product categories will be removed as Amazon looks to make auto-replenishment a reality. If shoppers run out of bleach or toilet paper, they can press a Dash button or ask Alexa. In the future, this will go even further by being automatically replenished. This will test brand loyalty in a way we’ve never seen before, while also freeing up space to focus on what can’t be done online – fresh food halls, cookery classes, cafés and restaurants. The experience will be highly personalised and utterly frictionless.

I believe entire product categories will be removed as Amazon looks to make auto-replenishment a reality. If shoppers run out of bleach or toilet paper, they can press a Dash button or ask Alexa. In the future, this will go even further by being automatically replenished. This will test brand loyalty in a way we’ve never seen before, while also freeing up space to focus on what can’t be done online – fresh food halls, cookery classes, cafés and restaurants. The experience will be highly personalised and utterly frictionless.

n reinvention and rightsizing – they see potential for at least 30 stores to be downsized, in a similar vein to competitors like M&S and House of Fraser.

n reinvention and rightsizing – they see potential for at least 30 stores to be downsized, in a similar vein to competitors like M&S and House of Fraser.